The brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright thought that their invention would never be used in war. The dropping of bombs from the sky, they considered, would result in such inhumane suffering that no military commander would countenance such an act of barbarity. They, of course, couldn’t have been more wrong.

In the Great War, aeroplanes were mainly used for observation. It wasn’t until Dutch aeronautical engineer Anthony Fokker in 1915 figured out a way to mount a forward-shooting machine gun on his flying machines to fired in sync with the propellor without damaging its blades, that dog fighting came into vogue. The German fighter ace Manfred von Richthoven, aka The Red Baron, flying a Fokker Dr I triplane downed eighty opponents before being fatally shot in the chest whilst in pursuit of two Canadian Sopwith Camels over the Somme on April 21, 1918.

Though the Great War heralded fighting and killing on an industrial scale, chivalry had survived. Von Richthoven was put to rest in the village Bertangles, near Amiens. His former foes served as pallbearers, salutes were fired, a guard of honor stood at attention, and all nearby Entente squadrons sent wreaths.

By the late 1930s, chivalry had died and the Wright brothers proven wrong. In what is considered the first aerial bombardment of a civilian population, the Basque village of Guernica was raised to the ground by 24 bombers piloted by officers of the German Condor Legion. The strategically located village, blocking the advance of the putschist troops of General Francisco Franco towards Bilbao, had been chosen as a target by Lieutenant Colonel Wolfram von Richthoven, younger cousin of the fighter ace.

The raid on Guernica, on April 26, 1937, during which about forty tonnes of explosives were dropped on the village, cost an estimated 300 lives. It caused worldwide indignation, including in Paris where celebrated Spanish expat painter Pablo Picasso felt such anger at the outrage that he just had to splash it on canvas. His resulting masterwork Guernica is widely considered the greatest work of art to come out of the twentieth century.

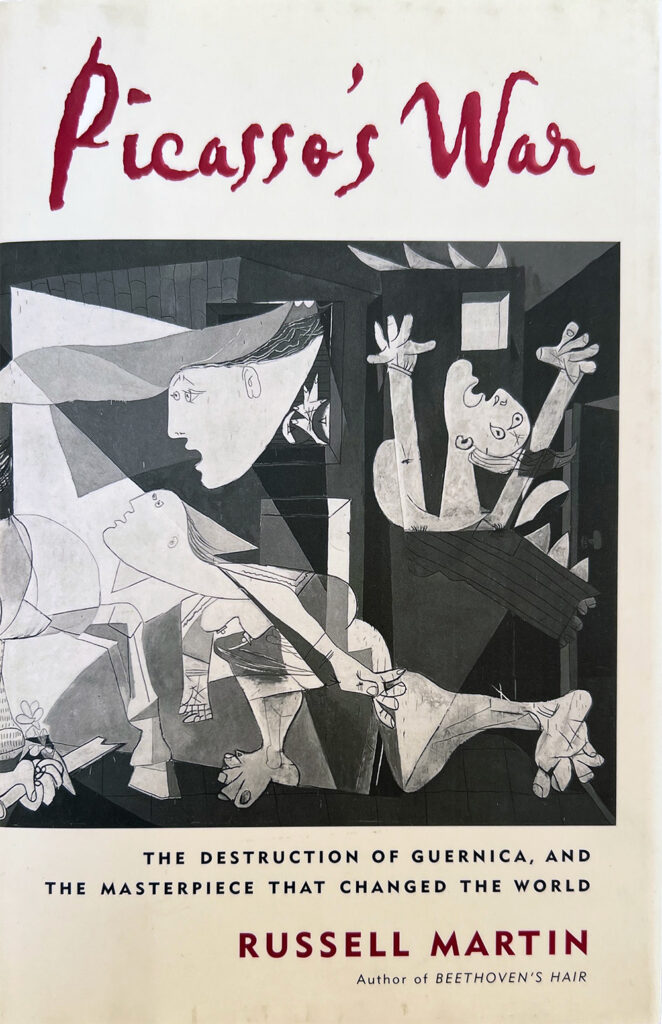

In his biography of the painting, Picasso’s War, Martin Russell focusses on the controversies that haunted the canvas for decades. First shown at the Spanish pavilion of the 1937 International Exposition of Art and Technology Applied to Modern Life in Paris, it was mostly overlooked or ignored. Those who did offer it a glance, found it overblown, incomprehensible, or simplistic. Only in later years would art critics agree that with Guernica Picasso had delivered his magnum opus. Guernica was loaned to the New York Museum of Modern Art where it was kept safe from Europe’s many tribulations. In his later years, Picasso requested that Guernica only be allowed to come home to Spain after that country had shed its dictatorial heritage. On September 10, 1981, the canvas finally arrived in Madrid under heavy guard. It has since been housed in a dedicated annex of the Prado Museum, protected by a bomb-proof layer of armored glass.

Book Details

- Picasso’s War: The Destruction of Guernica and the Masterpiece that Changed the World by Martin Russell

- Scribner 2003

- ISBN 978-0-7432-1989-1

- 304 pp